SA’s future? Moscow fantasy. Centralised. Not Nationalised.

Irina Filatova is a Russian professor who moved to South Africa in 1992 when she joined the University of Durban-Westville, now part of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. In this fascinating interview with Alec Hogg, the two explore the communist movement in South Africa and how it ties in with the Soviet Union. Filatova says the ideological influence of the Communist Party on the ANC leadership cannot be disputed and is evident if one goes through the ANC documents. Filatova is an accomplished author with seven books and many other publications to her name. Her last book The Hidden Thread: Russia and South Africa in the Soviet Era explored relationships between South Africa and Soviet Russia and won the Recht Malan Prize for Best Non-Fiction book of 2014 at the Media 24 Literary Awards. – Stuart Lowman

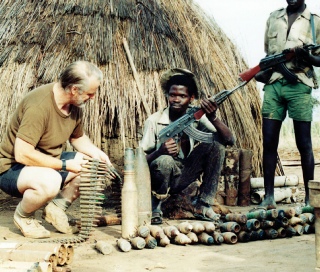

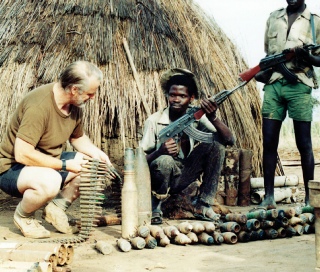

Russian Professor and author, Dr Irina Filatova, is married to RW Johnson, whom she met while at a braai in Durban.

Alec Hogg is in Cape Town and with Professor Irina Filatova. Irina you’re a Russian, living in South Africa now, but if we go back right to the beginning to where you started, were you born in Russia?

Yes. I was born in 1947 in Murmansk. That’s where the British convoys brought supplies of all kinds during the Second World War, and that’s how it is known to English-speaking people. I spent my childhood in Oryol, a town to the south of Moscow, and the rest of my Soviet life in Moscow.

As an academic interested in African affairs, what drew you to Africa?

I got interested in politics during my late school years. A lot of interesting things were going on in Moscow at that time and the city was politically alive. It was the era of Khrushchev’s thaw in the Cold War. Then the Cold War started to freeze hard again. There were fewer and fewer topics that could be discussed. But I found a very interesting outlet in something called ‘The House of Friendship’, a club in Moscow where you were allowed to meet foreigners. You couldn’t meet foreigners just anywhere. You were only allowed to meet them in certain prescribed places, such as this ‘House of Friendship’. There was an African seminar there, in which African students who studied in Moscow, participated. Sometimes African students from other cities came specifically for these meetings.

They got together for a seminar and they discussed everything under the sun. They felt free to discuss what was going on in Africa and in Russia, and if they didn’t like how their meetings were reported by the media, they protested. Of course, these protests were never published but still it was all very interesting and exciting. Russian students and academics were allowed to participate, so I started attending this seminar. Then I became their secretary and then I decided I to study Africa at Moscow State University.

It was an interesting time in relations between Africa and the USSR?

Yes, indeed. It is difficult to imagine now but at that time it seemed that Africa was the future. When my school geography teacher told us that by the time we finished school, the whole of Africa would be free, it seemed impossible. And when this happened there was so much hope, so much expectation for a better Africa and even a better world.

Was there a sense of déjà vu for you, when you came to South Africa in 1994, given what you had been through?

I actually came here in 1992. I started teaching at the University of Durban Westville in 1992, and there was indeed a lot of the sense of déjà vu. Not only in terms of a comparison with other African countries but also between South Africa and some events in Russian history. There was the same expectation of the revolution as in Russia before 1917. There was the coming of the democratic revolution ( “February 1917 revolution” in Russian terms), the same expectation of a more radical revolution (the ‘October’ revolution in Russian terms), etc. You could see these comparisons – and many more.

Going back to your time as an academic at Moscow State University, did you have a chance to meet any of the ANC leadership, who were in exile then?

That started much later, in the 1980s. At that time there was an opportunity to meet Africans and in particular South Africans at the Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee. The AASC called itself an NGO but in reality it was not one. It was practically a state organization. It closely coordinated its work with the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party. You had to be invited to its meetings, and not everyone was invited. Until the late 1980s such organisations were not really interested in academics: the attitude was, you do your work and we do ours. But trade unions and individual citizens contributed to such organisations financially and by organising meetings (e.g. against apartheid), for they wanted a better future for Africa and Asia, and they wanted to contribute towards that. In the late 1980s the Soviet Communist Party, the Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee and other such organisations began to get interested in involving academics in their activities. Discussions and seminars with ANC representatives followed. Suddenly, in the Gorbachev era and with the new political developments in Southern Africa, academic opinion began to matter. This was when people like me were asked to come and meet ANC people. I met a number of them, including some of the then leaders.

It appears today that there is in the ANC still a lot of the residue from that time that many of its members spent in the Soviet Union – calling each other comrade, for example; the use of a Soviet vocabulary and categories, applying Soviet-type policies and so on. Was this a deliberate learning process or was it just absorbed through ANC activists being there?

I don’t think that it was absorbed just by being in the Soviet Union. There are two answers really. First, the imbibing of Soviet doctrine, Soviet attitudes and the Soviet vision of the world were not necessarily connected to time spent by activists in the USSR. For these were all features of the ANC’s discourse and propaganda, particularly from the 1960s on. Such things were learnt through indoctrination which started back in South Africa and then continued during the course of the armed struggle. There was a very close connection between the South African Communist Party and the Soviet Communist Party. The ideological influence of South African Communists on the ANC leadership, of which they were part, cannot be disputed. You can see it still now in ANC policy, but it was there all the time as may be seen in the ANC’s historical documents.

Second, there was the same general understanding of the world as being divided into progressives and reactionaries, and into imperialists and socialists, with the bright future of the whole of humanity which was to come about through socialism and with the assistance of the Communist bloc countries. These were the same countries – Russia, the East European Communist states and East Germany – that were helping the ANC in its struggle against apartheid. So, obviously, for the ANC these were the good guys and therefore you had to listen to what they had to say.

And then there was, of course the Soviet example, the way it was presented to all African countries and to the ANC/SACP leadership. ‘Look what we have achieved through our socialist policies of centralisation, nationalisation, planning and so on.’They were seen by many African leaders, including South African leaders, as the example to follow and the short-cut to a bright and happy future. Of course, by the time the ANC came to power, they had accumulated a lot of experience of their own. Thy had seen how one African country after another had destroyed its economy by attempting to copy the Soviet example. They thought no, we are not going to repeat these mistakes. And indeed, they did not start nationalising immediately and all at once.

But the Soviet-era instinct remained: they had no alternative guide to take them into the future. The majority of ANC/SACP activists simply could not start thinking differently after a lifetime within the world of Soviet ideas and slogans. For the majority of such activists the future lay in – and still does lie in – ‘the second stage of the revolution’. Everything else was a preparation for this second stage – a decisive move to socialism. The whole idea of the national democratic revolution, which came from the USSR, means an incremental building of socialism. It remains the ANC’s official programme, and of course, the SACP’s as well. The odd thing was that at the time when the ANC came to power very few in the former USSR believed in such ideas.

The degree to which ANC people whom I met in Moscow were convinced that the Soviet example was the one to follow was quite startling. There were, for example, two seminars of the ANC held together with Soviet social scientists, organised by the Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee. A deputy head of the CPSU’s Central Committee attended one of these and tried to persuade the ANC comrades to be ‘careful’ with their economic policy and not to be in a hurry to nationalise. There was little understanding of the fact that some of the ANC’s Soviet advisers had begun to lose confidence in its own prescriptions.

Pallo Jordan, the head of the South African delegation, was the ANC’s main spokesman on nationality/ethnicity questions. When Soviet academics started to discuss ethnicity, race and nationality, and how such concerns were bound to remain important even in a liberated South Africa, there was, again, little understanding on the part of our South African colleagues.

We asked what they were going to do about protecting the rights of minorities and what they were going to do maintain good relations between ethnic and racial groups. The answer was that there were no racial or ethnic problems in South Africa. As soon as apartheid went, everything would be fine. There would be no animosity, no ethnic friction, no racial problems, no need to protect the rights of minorities. We were even told we paid too much attention to these issues because we were not sufficiently steeped in the ANC literature.

That’s pretty idealistic from the ANC’s perspective.

Very idealistic, indeed completely naive. But then again it was originally a Soviet idea that all national, ethnic and racial questions are created by imperialism, by capitalism and exploitation. So as soon as one did away with all that, no nationality problems could exist. Amazingly, the USSR was then pointed out as a good example of the resolution of national problem. The break-up of the USSR into fifteen different countries after 1990 showed just what a fantasy that was. There was also the idea that as soon as apartheid disappeared, capitalism would go with it. The argument was that capitalism was bound to collapse because it was inseparably connected with apartheid. History has shown how wrong that argument was.

That was indeed very simplistic. But you too must have been heavily exposed to this Soviet way of thinking. Did the post-1985 era of Gorbachev and perestroika come as a shock to you or was it inevitable?

Well, yes, I was exposed to the Soviet way of thinking. True, but when you are exposed to too much propaganda you start thinking differently. At least this often happens. My generation started to think differently long before Gorbachev. Some thought we must return to what was believed to be true Leninism – a more democratic and less authoritarian political and economic order. But then the Czech spring, which was exactly an attempt to create ‘socialism with a human face’, was suppressed by Soviet tanks in 1968. At home, the Soviet economy continued to slow down. We could see that Soviet socialism could not be reformed either economically or politically. And we could see that the system was not working. You just could not fail to come to the conclusion that the complete control of everything by one party: politics, the economy, ideology – every part of Soviet life – was a disaster. After all, it was Lenin who said, ‘monopoly leads to stagnation,’ and this is exactly what was happening. Many saw that the system did not and could not work. Long before the end of the USSR few still believed in the system.

It was painful to see ANC people coming there with the thought that Soviet-style socialism would work in South Africa. It was not a shock – we knew what their thinking was. But we could not tell them: don’t take this road. The deputy head of the International Department of the CPSU’s Central Committee tried, as I have pointed out, but he did not succeed. The ANC naively believed that they knew better. Who would have listened to young academics?

When Gorbachev’s reforms started, I thought he could never succeed. I thought he wouldn’t be allowed to go on. But he did go on and on. I could not believe what I was reading and hearing in the media at the time: I couldn’t believe this was possible. This was my reaction: not shock but sheer amazement.

Given all the evidence that the Soviet Union didn’t work, why is the experiment being repeated here in South Africa?

It hasn’t been repeated yet. I think that among the ANC leadership there are many who understand that they cannot repeat what was done in the Soviet Union. But many keep on dreaming. They think that the Soviet Union and the Soviet economy collapsed by chance. Or because Yeltsin and Gorbachev betrayed Soviet ideals. Both are singled out as traitors and Yeltsin even as a criminal. They would like to believe that if there were no Gorbachev then maybe the USSR would be alive and well even today. They also look at the example of China and Russia both of which have – or until recently had – impressive rates of economic growth. It is rather reminiscent of the 1930s where the dictatorships of Germany, Italy and the USSR seemed to be doing better than the democracies. For both the Chinese and Russian economies are centrally controlled. Privately run perhaps, but strictly controlled by the centre. For the moment this seems to be working, while many Western economies are barely growing. At least, this was the idea until recently and the leadership of Cosatu and the SACP were greatly cheered by it. Now that China is slowing down and Russia’s economy actually shrinking, while the British and American economies are showing healthy growth some re-think may be necessary. But those who want to believe in the virtues of centralized control will doubtless continue to do so.